|

|

|

|

Chronology 1941 - 1945

1941 – 1946 Cuba, forced exile to the native land Return to flamboyant nature (1941 – 1943)

Sans Titre, 1941

Upon their arrival, Lam reunited with his family – his mother, Serafina, and his sisters Eloísa, Teresa and Augustina. The prodigal son had returned. Despite this moving reunion, Lam felt an uneasy sense of no longer belonging, of being uprooted. He hardly recognized his own country. Havana had changed “with its white capitol, the mark of America, its banks, its palaces, its luxurious European shops.” The city flourished but it was all mercantilism and the cultural climate was deplorable, dominated by art that was either overly academic or folkloric. He began to reconnect with a past he thought had disappeared and managed to reconstitute a fluctuating core of friends, acquaintances from the past and other exiles from Europe who arrived before him: Carlos Enríquez, Mario Carreño, currently a teacher at the San Alejandro, Nicolas Guillén, Manuel Altolaguirre and Alejo Carpentier, whom Lam would see frequently; and on their way to Mexico, Remedios Varo and Benjamin Péret who spent the autumn in Cuba. Lam maintained an epistolary relationship with his other friends, as promised. Breton spoke highly of Lam's painting to the New York gallery owner Pierre Matisse who took him on contract and proposed to exhibit his work the following year. A return to work was imperative, but how would he go about it? “I thought back to Europe being invaded by the Nazi army with great sadness... For me, seeing Europe had been everything. When I came back to Cuba, I was taken aback by its nature, by the traditions of the Blacks, and by the transculturation of its African and Catholic religions. And so I began to orientate my paintings toward the African.”2

Exposition Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, 1942

To begin with, he reconnected with his natural surroundings – the rows of flamboyant trees, fields of sugar cane – and then with his compatriots. He reflected on the striking contrast between the frivolity of Havana's tourism and the miserable condition of the blacks in the countryside, for whom discrimination appeared to have worsened with Batista: “What I saw upon my return looked like Hell.” “All the drama of the colonialism of my youth resurfaced in me”. Lam turned to painting, not as an escape but as a way of denouncing, of contesting what he was witnessing. Like a lone soldier he set about painting the drama of his country, the cause and the spirit of the Blacks, their aspirations for liberty. And, to stand out from all folklore and its pictorial manifestations as advocated by Cuba's political parties, he began to invent his own language. In his canvases, surreal, phantom-like, spectral, vengeful, denunciatory, almost hallucinatory figures rose up, playing out their drama within exuberant vegetation where faun and flora blend and multiply. His visions thus re-actualized what had been subjugated and shrouded in the depths – images he hoped would be “capable of disturbing the dreams of the exploiters”. For, in his mind, a true painting “sets the imagination to work.” And hence, thanks to his project, Africa could re-enact its entry into the Caribbean. In February, 1942, Lam and Helena moved into a large house surrounded by the luxuriant vegetation of its garden, giving him an ideal space to paint. He set about painting with great fervor, in lieu of the exhibition being planned in New York. Pierre Loeb and his family, who also spent the war years exiled on the island, were happy to reconnect with them. In discovering Lam's most recent paintings, Loeb saw this forced exile in a positive light. “It was his chance. He renewed his contact with the tropics, which he breathed and penetrated, becoming one with it.” Santería and orishas (1942 – 1943)

Homenaje a Jicotea, 1943

It was also a return to the old beliefs of his childhood. He was introduced to Lydia Cabrera, an anthropologist and specialist in Afro-Cuban culture, who had been combing the island in her effort to compile and safeguard the songs and legends of the first Blacks to have come to the island. Alejo and Lilian Carpentier became the couple’s closest friends. Lam thus renewed his ties to the myths and rituals of his godmother Antonica Wilson. His sister Eloísa, very well versed in the cults of Santería, arranged for the group to attend initiation ceremonies and ceremonial dances to the sound of the beating drums. Cabrera, Carpentier and Guillén were convinced that the deported religion of African gods was one of the founding elements of Cuba's cultural identity and at the origin of “magic realism” – a concept Carpentier created around 1940, which defines the cultural specificity of the Hispanic American world, with its roots plunged in the primitive, in folklore and myth – the marvelous that infuses its popular culture but also the marvelous adopted by Surrealism. Lam, by now fully sensitive to this, having fostered his own intimate relationship to the unconscious, re-established his ties to the practices of seers and magicians. And his figures are in large part inspired by the Orishas (divinities of nature from the Yoruba religion). During this period of re-acquainting himself with the past, Lam also showed great interest for the new cultural developments. He often sought out the company of the Cuban poet and writer Virgilio Pinera, director of the review Poeta in 1942, the Cuban poet José Lezema Lima, founder of the review Nadie Parecía in 1941 and the soon to be review Orígenes (1944 – 1954) with José Rodríguez Feo. And his close friends, José Luis Gomez Wangüermet, Jorge Manach, Gaston Baquero, José Hernandez Meneses, Roberto Juan Diago Querol and Manuel Moreno Fraginals. He met Pierre Matisse for the first time who had come to Cuba to personally accompany Lam's paintings to New York. And lastly, he had many friends among the foreign artists who were living in exile such as Robert Altmann. Toward the end of the year, after multiple trials with gouache and tempera, he began to compose La Jungla, the largest painting he had ever painted up to that point. The Scandalous Jungle (1943 – 1945)

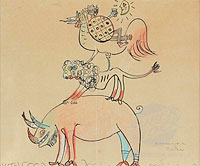

The Jungle, 1943

The completed painting of La Jungla captivated his friends. Pierre Mabille, who was enjoying a brief stay on the island, compared the importance of Lam’s work to Paolo Uccello's discovery of perspective. He claimed it was a painting “in which life bursts forth, unfettered, dangerous, poised for all possible combinations, all transmutations and forms of possession.” No one, it seems, failed to see the impact it would have: “Dream of Eden,” according to Breton; “delirious vegetation,” according to Leiris; “revolutionary unrealism,” Fernando Ortiz; and later Max-Pol Fouchet wrote: “a barbaric poem, monumental, superb.” It's a painting that describes “the convulsion of man and the earth”. In other words, Lam's painting entered into resonance with the poetry of Césaire who called upon him to translate his Cahier d'un retour au pays natal into Spanish but Lam chose, instead, to entrust Lydia Cabrera with the task. Retorno al país natal, with a preface by Benjamin Péret and three drawings by Lam, was published in Havana in 1943. Lam was pleased to see Mabille again who was in transit between Haiti, where the doctor, with his great knowledge of civilizations, had completed a series of conferences on Physical Anthropology and Biotypology, and the Yucatan, on a mission for the Institute of Ethnology. Mabille steered Lam to hermetic texts which, according to his new theory, had a link to the practices of voodoo (Paracelse; Martínez de Pasqually; Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin). Mabille and Loeb, both very interested in esotericism, also encouraged him to study the ties between religion and spiritism in Santería – disciplines related to the subconscious – but also to draw parallels between Western and Oriental philosophies, primitive civilizations and ancestral memory. On their way back, Mabille and Loeb invited Lam to accompany them to Santería and Abakuas ceremonies (the Abakua brotherhood was formed in the 19th century by the Africans of Nigeria with the aim of penetrating the meaning of the mysterious language of the tam-tams). They were accompanied by Carpentier who was writing a piece on musical instruments and Cabrera who was recording the songs of African slaves. These experiences and their guidance inspired Lam to use Nanigo symbols in his paintings.

Lam in his studio, Havana, Cuba, 1943, (The Jungle)

This rich entourage filled Lam with inspiration as he continued to paint with fervor. Despite the fact that the New York exhibition of La Jungla in 1944 had created a scandal, he approached his subject with absolute freedom. The slight improvement in the political situation with the election of Ramon Grau San Martin as President combined with the death of his mother were undoubtedly factors in pushing Lam to work twice as hard. He married Helen Holzer and participated in the foundation of the committee Artistas Plasticos de Ayuda el Pueblo Español with the painters Ramos Blanco, Carlos Enríquez and René Portocarrero. He also became involved in the domain of music, becoming the Vice-President of Havana's Chamber Orchestra (Philharmonic orchestra), which invited the conductor Erich Kleiber to Cuba. Kleiber later brought over the composer Igor Stravinsky. Meanwhile, the maverick Russian violinist Jascha Heifetz joined the orchestra, giving Lam the occasion to meet him. Just as the MoMA of New York bought La Jungla and hung it alongside a no less important work – Picasso's Les Demoiselle d'Avignon – Sagua la Grande nominated Lam the title of “citizen of honor.” He chose to be present for the ceremony and used the occasion to show Helena around his birthplace of Sagua. His artistic activity expanded as he began experimenting with new techniques such as lithography. Lam made a lithograph for the cover of Loeb's book Voyages à travers la peinture and to illustrate a poem by Yvan Goll – another European exile. Yvan Goll had stayed with Guillén before meeting up with Breton in New York. Lam also designed the covers of the reviews Orígenes and View (n°2) – a special edition dedicated to “Tropical Americana” and presented by Paul Bowles whom Lam met in Cuba. In May, Pierre Loeb had nothing but praise for his painter friend, writing in Tropiques: “Lam knows how to draw and paint, he's read everything, he knows music inside out, he is the brother of our most sensitive modern poets; […] the magic we most desire, implore, search for, is within him.” Anne Egger (Translation by Unity Woodman) (2) It is important to remember that African art was forbidden in its representation or reproduction during the slave period in the Antilles; likewise, it was forbidden to weave or sculpt. The slave, exiled without objects, had only the option of singing, dancing or recounting poems and fables |