|

|

|

|

Chronology 1938 - 1941

1938 – 1941 Capital encounters – France

Still life, 1938

When he arrived at Paris's central station, Gare d'Orsay, he found lodgings in an attic room in the Hôtel de Suède on the Quai Saint-Michel, not far from the police headquarters, which would soon become, his being a foreigner, an all too familiar place. He explored Paris on foot, meeting up with his old friends Mario Carreño, Alejo Carpentier and Pablo Neruda who, along with César Vallero, had founded the “Groupe hispano-américain d’aide à l’Espagne” (The Hispanic American Group to Help Spain). He visited the Louvre which was currently exhibiting English painting with works by Reynolds, and then the Galerie des Beaux-arts which was exhibiting the Impressionists Renoir, Cézanne, Van Gogh and others. Lam was both intimidated and fascinated by the idea of meeting Picasso. But even before the set visit to his studio on Rue des Grands-Augustins, as Lam clutched his letter of introduction from Manolo, Picasso welcomed him with open arms; indeed, for both of them, it was “love at first sight.” An unwavering friendship was born, a deep bond between these two artists who had traveled opposite but converging paths, joined in their struggle for creative freedom. “My meeting with Picasso and with Paris was like an electric shock...” For Lam, Picasso represented the epitome of boldness and his entry into his artistic life was like meeting an “instigator of freedom.” When Lam visited Picasso's studio, he was captivated by his African art collection, especially a helmet mask of the Baule tribe (Ivory Coast), a round head with antelope horns and a crocodile's jaws. What drew him to Picasso's art was the “presence of the aesthetic and spirit of African art.” “Negro art” was a revelation to Lam who was immediately sensitive to its power and energy and its striking independence from the real. Faced with Picasso's art and what had become a general fascination for the archetypal figures of ancient civilizations, Lam brimmed with questions, prompting Picasso to introduce him to the young poet and ethnologist Leiris, the person he felt was most suited to guiding the Cuban painter in his quest for understanding “Negro art.” Leiris was a former surrealist, whose circle of friends included Pierre Mabille and the sulfurous Georges Bataille, the brother-in-law of the art dealer Daneil-Henry Kahnweiler. That very evening, Lam dined with Leiris, Picasso and Dora Maar, in what was the first of almost daily gatherings, until Picasso returned to the south of France. Picasso introduced his Cuban “cousin” to Henri Matisse, Fernand Léger, Georges Braque, Nusch and Paul Eluard, Tristan Tzara and the Catalan art critic Sebastien Gasch.  Michel Leiris was employed by the Musée de l'Homme, the city's ethnological museum, in its Black Africa department. With his wealth of knowledge about the magic of the “savage arts,” Leiris guided Lam through the museum's new halls and its reserve collections of African statues, Oceanic masks, Australian totems…. Here at last, Lam was face to face with art untainted by the tyranny of a bourgeois intellectualism. Through Leiris, he met the scholars Georges-Henri Rivière, who was also passionate about music – himself a jazz pianist – and Léon Gontran Damas, who, along with Césaire and Senghor, was one of the fathers of Negritude. Senghor was passing through Paris after a mission in Guyana. Leiris steered Lam to the city's specialized galleries, to major exhibitions, and to Pierre Loeb's and Charles Ratton's collections. During the summer, Leiris introduced him to André Masson who had just returned from several years in Spain. He also met Joan Miró and other artists affiliated with Surrealism, among them Oscar Domínguez and Victor Brauner. Instead of letting himself despair about the international situation – news from Cuba, the Munich accords – he plunged into his work: “I painted both night and day, although I wasn't ready to show my work. Paintings piled up in my small hotel room and I could no longer, so to speak, move or paint.” In the autumn, he was presented to André Breton and Jacqueline Lamba; they had just returned from Mexico. His first visit to the studio on the Rue Fontaine was a magical experience. Lam was captivated by Surrealism and the opportunity it offered to access the unconscious through automatic writing: “Surrealism allows for deliverance from cultural alienation,” he once said, and for unearthing one's true self.

Mother and child II, 1939

The doors of Surrealism had opened to him. In a café, he met up with Benjamin Péret, who had fought in Spain in the Poum division, and his companion Remedios Varo, as well as Yves Tanguy and Hans Bellmer, who had escaped Nazi Germany. He met Roberto Matta, Wolfgang Paalen and Esteban Franès Kurt Seligmann – all present at the exhibition of pre-Colombian art organized by André Breton at Charles Ratton's gallery entitled Mexique. Lam was welcomed into a circle of artists and intellectuals who had spent their lives militating against racism, against any form of discrimination, against all abuses of the colonial system.... It was a milieu that had already taken stock of the notion of oppressed identity and whose international resistance applied to all forms of fascism. His work became more “personal” in scope during his Parisian period. He painted frontal, hieratic figures, at once minimal and monumental. These paintings are totemic representations of loss and tragic portrayals of maternity. In their formal simplicity, already begun in Spain, they show undeniable affinities to the work of Picasso. “Our plastic interpretations intersected,” Lam would explain later, and even went on to claim there had been a “saturation of spirit.” He felt a sense of freedom. Masks emerged in his paintings and the act itself of painting proved to be a means of expression for describing the condition of his soul, its pain of loss. The paintings of this period all show isolated, schematic and often speechless figures – emaciated, austere and suffering. He expressed himself as an atheist, fascinated by the magic arts, the magic of animism. News reached him of the fall of Barcelona on January 26, 1939, dashing all hopes of a Spanish republic. Among the 500,000 refugees who fled into France, he happened to meet Helena Holzer who had just reached Paris. Breton introduced him to the erudite scholar Pierre Mabille, both an ethnologist and a surgeon. During a rendezvous at the restaurant Les Deux-Magots, Mabille sensed that hiding behind Lam's reserve was a philosophical and cultural astuteness. He was enthralled by the elegance of the Cuban artist's drawings and talked of their “staggering freedom.” Similarly to Christian Zervos, the publisher of Cahiers d'art, the gallery owner Pierre Loeb, who was by then a close friend of Lam’s, offered to sign a contract with him for the second time and decided to exhibit his work. Newly immersed in this supportive artistic brotherhood, Lam found the stimulation and confidence he needed to at last show his work, which he had hesitated even to show to Picasso: “I'll never forget that moment. I keep it engraved in my heart and in my memory and go back to it again and again, like the great paintings and books that made me the man I am.” Picasso “showed his approval by freely linking his arm around my shoulder where I felt his hand flutter on my back. At which point I heard him say, 'I was never wrong about you. You are a painter.” Picasso found him a studio in the 15th arrondissement on Rue Armand-Moisart, near Montparnasse. He worked there often and with greater spontaneity, a place where he received such friends as Carl Einstein, Pierre Loeb, Picasso, Dora Maar, Jacqueline Lamba and André Breton. The exhibition at the Galerie Pierre took place from June to July, 1939, and was viewed by the Paris art scene as a revelation. Exodus and Collective Works (1940 – 1941)

Mascara, 1940

Lam continued to paint all the way up to the lightning offensive of the Germans in May, 1940. Being of German nationality, Helena was arrested and consigned to the Gurs Camp (in the Pyrenees). When the enemy army headed toward the capital in early June, Lam, who was deeply distraught by having to leave, nevertheless followed the exodus of Parisians and began the long trek on foot to Bordeaux. The Armistice, signed by General Pétain on June 22, incited him to continue on to Marseille where over a hundred intellectuals hostile to the Nazi regime were trying to leave the country, among them many of his surrealist friends. Helena, once freed, joined him there. These various personalities were given assistance from the Emergency Rescue Committee headed by Varian Fry and Daniel Benedite, which allotted Lam a small pension. Although Lam was preoccupied by the general situation and anxious about having to make his morning rounds to the prefecture, his stay in Marseille proved stimulating: “I made many strong ties with the surrealists during the Occupation.” Together they formed a “very large family, with Breton and Benjamin Péret, Victor Brauner and Domínguez, who was Spanish and my great friend.” Among his other friends were Max Ernst, Hérold and Mabille. “I was impressed by the poetic aspect...a great combat for creation...we worked as a group for almost a year. It was the period of cadavres exquis and many inventions.” The friends came together at the Villa Air Bel or at the Brûleur de loups café on the old bridge. They created collectively to pass the time and to alleviate their anxiety: drawings, collages, cadavres exquis, automatic writing, games of truth and a new Marseille tarot. They discussed and shared their readings. ![Sans Titre, [Fata morgana] Serie from the "Carnets de Marseilles", 1941 Sans Titre, [Fata morgana] Serie from the "Carnets de Marseilles", 1941](../../Img/drawings/D-41.X_vignette.jpg)

Sans Titre, [Fata morgana] Serie from the "Carnets de Marseilles", 1941

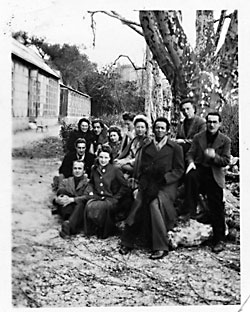

During the winter of 1940 – 1941, Lam and Breton developed mutual respect for each other. The poet had the gift of recognizing budding talent and sensed Lam would create a visionary world in the future. When Breton asked him to illustrate his poem Fata Morgana, a poem full of his Mexican impressions, Lam set to work and produced hundreds of ink and pencil drawings, which are particularly prescient of his future signature style. In March, six of his drawings accompanied the printing of five copies (published by Editions Sagittaire), but the book was blocked by the censorship commission, forbidden on the grounds that Breton was suspected of being an anarchist and that his work was a “negation of the spirit of national revolution.” Its illustrator, they claimed, represented the incarnation of both degenerate art and racial impurity. But departure was imminent and a last exhibition-sale was organized of their paintings in the garden of the Villa Air Bel. Peggy Guggenheim bought two of Lam's gouaches. He thus left the country with a few bank notes and, above all, the encouragement of both Picasso and Breton – a fine gift for braving his exile. The “Ship of Fools” sets sail for the Caribbean (1941) On March 25, 1941, the little steamer Capitain Paul-Lemerle headed west, on board ship Wifredo and Helena, André Breton, Jacqueline Lamba and their daughter Aube, Victor Serge, once a close companion of Lenin's, his family, Anna Seghers and 350 other intellectuals threatened by the Vichy regime and the German police. “When the time came to embark the quayside was cordoned off. Helmeted gardes-mobiles, with automatic pistols at the ready” – or so reads an episode described in Tristes Tropiques by one of their companions, Claude Lévi-Strauss. Poetic call at Martinique I

Marseille, first raw from left to right : J. Hérold, H. Lam, W. Lam, A. Gómez. Second raw : Pino, H. Gómez, friend of Pino, J. Breton, A. Breton. Third raw : O. Domínguez and his friend.

On April 24, the passengers met with an icy reception in Martinique. Viewed by the Vichy regime as “deserters,” they were immediately interned at the Lazaret camp, where they spent over a month – the fate of all foreigners and French people suspected of leftist leanings. Jacqueline, André and Aube Breton, however, were allowed to settle in Fort-de-France, where they were soon met by André Masson and his family, who arrived on a later boat. On some days, Lam and Helena were given leave to join their friends in the capital. Breton discovered the review Tropiques and met its founders Suzanne and Aimé Césaire and René Menil – a key encounter for all involved. Breton and Lam embraced Martinique's great poet as the messenger of a new era; as for Césaire and Lam, they were indebted to Breton for his “brazenness,” for pointing them to such uninhibited choices, and for saving them precious time. Surrealism had opened the way for them to invent forms of expression and representations deeply anchored in their heritage: an approach steeped in the vernacular of Antillean culture and the animism inherited from Africa. Surrealism was a Western technique for becoming African. For Lam, these encounters put his hesitations to rest once and for all. Césaire organized excursions of the island, and Lam took in its exuberant vegetation, bursting with life, with a sort of fascination: “It was his first true meeting with tropical nature,” Césaire would recount. He was fascinated by the “savage beauty of the island, the generous slopes of its mountains, rich with such varied, dense vegetation, overflowing with life, with sap, making each plant swell, fantastical intertwining and tangled trees,” wrote Loeb. There “he was revealed to himself. The tropical way of looking at things had replaced the Spanish. He now saw this landscape and it created a deep shock. His painting changed.” While Lam discovered Césaire's exalted world of imagination, Césaire, for his part, declared, “Lam is a poet” and “a man of the Antilles” about to plunge more deeply into his Afro-Cuban identity. Césaire called him “the great artist of Neo-African painting.” Suzanne and Aimé organized a reading that again had significant impact on the Cuban painter... The Cahier d'un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land), which Césaire wrote in 1938, was a song praising the dignity of the Negro, a great affirmation of his being and genius, uniting “the barest, most direct outcry from the bowels of man of the misery of the Black man in the very heart of this floral magnificence.” Lam found an echo in this fight against injustice and colonial despotism championed by Césaire, Senghor and Damas... He had essentially found a brotherhood. The review Tropiques also embraced and inaugurated “the passage of Wifredo Lam, the astonishing Negro Cuban painter in whose work we find, alongside the best teachings of Picasso, a curious and wide intermingling of Asian and African traditions” (issue n°2, 1941). A stop-over at Saint-Domingo On May 16, 1941, the exiles once again embarked on a ship, a cargo ship this time, the Presidente Trujillo, which took them to Guadeloupe where Mabille had been living for a year, although he was already preparing to leave for Haiti, weary of living under the Vichy regime. Their voyage continued on to Saint Thomas and Saint-Domingo, a port of call to obtain their visas. Lam met Eugenio Granell who was living in exile there. He interviewed these erudite figures – Breton, Victor Serge and Mabille – for the newspaper La Nacíon. During their daily meetings, others soon joined them: the abstract Spanish painter José Gausach, the Austrian portraitist, George Hausdorf, the sculptor Manolo Pascual who taught at the National Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1939, and the Dominican artists Yoryi Morel (a master of local folklore), Jaime Colson (who had met Braque and Picasso in Paris) and Dario Suro (a student of Diego Rivera's). The friends had to part ways as only the Breton and Masson families were given permission to continue on to New York, while Lam and Serge, who did not receive visas for Mexico, had no choice but to sail on to Cuba. In August, after five months of this journeying and an absence of seventeen years, Lam reached the shores of his native island. Anne Egger (Translation by Unity Woodman) |