|

|

|

|

Chronology 1923 - 1938

1923 – 1938 Spain. In search of his art The discovery of the old world and his artistic training from master works (1923-1935)

Self portrait

Wifredo arrived in Spain in late 1923, only twenty years after the country lost Cuba, its last colony. In Madrid he made acquaintances with Fernando Rodriquez Muñoz, a well-educated medical student, a touch bohemian, who introduced him to his circle of friends – for the most part art lovers – most notably Baldomero and Faustino Cordõn, a future biologist. Thanks to his letter of recommendation, Wifredo came into contact with the Director of the Prado, Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor, an official portraitist of noble birth and a professor at the Real Academia de Bella Artes. He invited Wifredo to study at the academy which introduced the young painter to an artistic climate far removed from the modernity he had hoped to find. He turned to the masters for inspiration on his many visits to the Prado: the mannerist portraits of El Greco and Velázquez, the mythological scenes of Poussin, Goya's “horrors of war” – what Lam termed “visions of crimes as spectacles of the injustices of a delinquent militarism” – the critique of injustices by Breughel in The Triumph of Death, the hybrid creatures of The Garden of Delights by Bosch, engravings by Dürer – the great witness to the anxiety of his epoch and its superstitions. These artists of revolt with their painted discourses against all forms of tyranny spoke to him directly as he patiently copied them, sending the copies to Sagua to justify his grant. He was also moved by what he saw at the Archeological Museum, which marked his discovery of prehistoric art. Every day, when he left San Fernando, he would make his way to the Alhambra where he was simultaneously enrolled in classes at the Escuela Libre de Paijase founded by Julio Moisés. These workshops were far more experimental approach, thanks to the influence of its non-conformist painters Benjamin Palencia, Francisco Bores, José Moreno Villa and Salvador Dalí. With General Machado's rise to power in Cuba, Lam lost his grant and entered a period of dire financial hardship. He began to offer his services as a more or less classical portraitist to the aristocratic milieu of Sotomayor's circle. During the summer of 1925, his friend Muñoz invited him to visit his family in Cuenca. This small Medieval town, perched on a steep spur in the mountains southeast of Madrid, struck a chord in Lam who set about painting its arid landscape and the poverty of its peasants, perhaps reminders of the disinherited people of his own island. He spent several months in Cuenca, joined by his friend the portraitist Jaume Serra Aleu. They settled in a small studio in the town's center and mixed with the local artists and intellectuals (Compans, Marco Pérez, Fausta Culebras, Zomeno, Eduardo de la Rica, Vazquez Díaz, Serra Abreu, Rusinol…) who regularly met up at the Iberia Hotel or the Escobar bookshop. For the first time, Lam felt connected to an artistic community, and new influences began to enter his work: the Catalan symbolists (Herman Anglada Camarasa, one of the major interpreters of Andalusian neo-regionalism – and Nestor), followed by the art of Cézanne.

Eva Piriz and Wifredo, Madrid, 1927

Upon his return to Madrid, he discovered the Vallecas School which was seeking a renewal in its approach to the Spanish landscape. Its founders, Benjamin Palencia and Alberto Sanchez were joined by Canaja and Maruja Mallo and supported by Manuel Angel Ortíz and Guillermo de la Serna. Lam's paintings of the local landscape and abodes during the summer of 1927 spent in the region of Cuenca are very much in this vein. Shortly afterward, the talk among the avant-garde artists of Madrid openly addressed Surrealism—a movement created in Paris four years earlier. The painter Benjamin Palencia, recently returned from Paris where he had met Picasso, Braque and Matisse, was the first to show works of Surrealist inspiration. Other painters were soon to follow: José de Togores and José Moreno Villa. Always curious about the latest tendencies in art, Lam made attempts at automatic writing. This was also when he made his discovery of the masks and sculptures of Guinea and the Congo as they were on exhibit at Madrid's archeological museum. In 1929, a large exhibition of Spanish painters living in Paris was held at Madrid's botanical gardens with the sculptors Apeles Fenosa and Pablo Gargello, the painters Juan Gris, Manuel Angel Ortiz, Pablo Picasso and Pedro Pruna. What struck the young painter above all was the formal energy that emerged from the works of Picasso. According to Lam, the revelation was both of a pictorial and political nature. It made him want his own paintings to convey “a general democratic proposition […] for all people.” This declaration undoubtedly reflects how the painter felt about the alarming social situation in Cuba under Machado's dictatorship, a situation he was able to follow closely from the letters he received. In the company of his friends Muñoz and Cordón who exposed him to the ideas of Marxism, Lam awakened to a new political awareness. Likewise, he began frequenting the Sunday gatherings of a group of Latin American belonging to the Hispanic American University Federation. Wifredo Lam and Eva Piriz, whom he had met two years earlier, were married. Political and domestic economic crisis (1930 – 1933) The economic crisis in Spain had dire consequences for Lam’s own financial situation. Despite the penury of the newly weds, however, the birth of their son, Wilfredo Victor, brought them much joy. The painter flourished in his new family life, taking a sharp interest all the while in the world of art. The Autumn Salon presented the symbolist and surrealist works of Angeles Santos that may well have inspired his own. But his happiness was short lived: Eva and the child both died of tuberculosis in 1931. This double loss plunged Lam into despair. In his letters, he speaks of being “disgusted,” “revolted” and “neglectful.” And while a trip to Cuba to see his family again was much on his mind, the conditions were far from favorable: the repressive politics of Machado reigned over the island even as Spain was on her way to becoming a Republic, following the overthrow of the monarchy. Only the support of his friends Faustino Cordón and Anselmo Carretero, the latter an engineer in training, kept him from going under. They found him commissions for portraits to ensure he had enough money to eat. But he worked little, choosing instead to spend his time reading, in particular historical and ethnographic books on Africa and slavery. During the summer of 1931, he and his friend Anselmo Carretero made a trip to León, a mountainous region in the northwest of Spain where they befriended a small group of local artists. Gradually, Lam regained his spirits. The great discoveries of this period included the latent cubism of Cézanne, the exotic primitivism of Gauguin and the impressionist naturalism of Franz Marc.

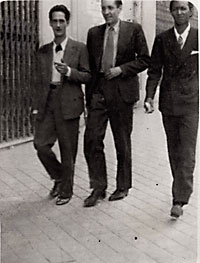

C. Enrique, W. Lam, A. Carpentier

In Madrid, Lam and Faustino Cordón frequented the café on the Gran Via, a meeting place for a wide range of intellectuals: Juli Ramis (a painter he shared a studio with), the writers Azorin (José Martinez Ruiz) and Ramon del Valle-Inclan, the poets Federico García Lorca and Jorge Guillén, the Cuban painter Maria Carreño, the Guatemalan journalist and poet Miguel Ángel Asturias, an amateur of pre-Colombian culture. Their debates focused on the emerging Republic and their growing concerns about the rise of the conservative opposition and of fascism in general. These fruitful meetings reawakened Lam's enthusiasm, but did nothing to assuage his fears about Cuba, as letters from his family and friends brought him news of a new wave of terror sweeping the island – assassinations, torture, prison, labor camps but also of the organized resistance and press campaigns against Machado's dictatorship. Cuban exiles in his entourage corroborated these reports. In 1933, on the brink of disaster, staying informed about world events was imperative – one could no longer be a bystander. Hitler was nominated Chancellor of the Reich and new anti-Semitic laws were enforced; the Cuban people succeeded in bringing down Machado and forced the “Tropical Mussolini” to flee to the Bahamas but within a month Batista's military coup d'état had already set in place another dictatorship; in Spain, the elections put the rightwing back in power for a three-year term – an increasingly extremist right wing. Politically, Lam stood firmly to the left, decisively Marxist in sentiment but free of dogmatism. He participated in the first exhibition of revolutionary and anti-fascist art at the Athenee and made contact with different activist groups fighting imperial dictatorships: the Asociacion general es estudiantes latinoamericanos (AGELA), the Organisacion anti-fascistes, the Federation universitaria española and the Comiyé des Jovenes Revolucionares Cubanos to which his compatriot in exile and new friend, the self-taught painter Carlos Enríquez Gómez, belonged. He was also introduced to the Cuban Alejo Carpentier, who had been living in Paris for five years. Carpentier, a musicologist and writer had his novel Ecue-Yamba-O published that same year Ecue-Yamba-O – among the first Afro-Cuban novels. At the Prado, Wifredo met Balbina Barrera, an amateur painter who, like himself, enjoyed copying the master painters. She and Wifredo would remain very close for several years. Crisis of inspiration 1934 – 1935 Lam entered a period of self-doubt – at once an existential and artistic crisis – that prevented him from painting. He continued to read a great deal: classics of the Spanish language; contemporary poetry, including an anthology of Iberian poetry prefaced by Lorca who attempts to explain the secret of the Góngora language, the Persian poet Omar Khayyâm and the pre-Romantic William Blake; Thomas Mann; Russian novels from the 18th-century up to Nikolai Gogol. He also read various works on historical materialism, exploring the revolutionary writings by Russian and German theorists his friends Fernando Muñoz and Faustino Cordón recommended to him. And furthermore, he studied books on art covering the work of Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse and the German Expressionists, particularly Franz Mark. In his modest one-room flat in Madrid, Lam struggled with his doubts. For a year, he painted the view from his window, trying out different chromatic formulations, which are primarily influenced by Matisse. He spent the summer of 1935 in Malaga – a small Andalusian seaside resort and the birthplace of Picasso – with Balbina and her six children. The city's Museo de Bellas Artes, founded in 1923, presented Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque collections with works by Ribera and Pedro Mena. On his way back to the capital, he passed by Grenada to visit the Alahambra, undoubtedly invited by Lorca. Back in Madrid, where his friends welcomed him, he discovered the first issue of Caballo verde para la poesía, founded by Pablo Neruda and Manuel Altolaguirre. The combat for liberty (1936 – 1938)

W. Lam and B. Barrera, Spain, 1935-36

In February 1936, with the victory of the Frente popular and its wave of social reforms, there was much celebration but Lam was still faced with his creative block. In light of the anti-Republican military insurrection on July 18, he saw painting as secondary. The Spanish Civil War had begun. In three days, a third of the country was overcome by Franco's partisans, but Madrid and Barcelona put up strong resistance. Lam learned of the assassination of Lorca in Grenada and Neruda's recall from Madrid, while others arrived to support the Republicans: Carl Einstein who joined the Durutti Column or the Cuban war correspondent Pablo de La Torriente Brau, who died in combat in December. Lam and his friends signed up to the war effort. Following the example of Mario Carreño, Lam began designing posters for the ministry of propaganda to extol the glory of the Republicans and then participated in the defense of the city that had come under siege in November. Above all, there was a need for ammunition. His chemist friend, Faustino Cordón, found a position for him in an arms factory and he was given the job of assembling anti-tank bombs.

Lam with two milicians, Madrid, 1936

After six months of intensive work handling explosives, Lam suffered from poisoning due to his contact with the chemical products. In March 1937, he was sent to convalesce in the sanatorium of Caldes de Montbui, north of Barcelona. On his way through Catalonia, he stopped briefly in Valencia where he met Perez Rubio and Joseph Renan. As the Director of Fine Arts for the Spanish pavilion for the International Exhibition in Paris, Renan commissioned a painting from Lam on the theme of the war, but by the time Lam completed La Guerra civil it was too late for it to be exhibited. He continued on through Barcelona in the month of May when the anarchists of the Poum were being sacrificed by the representatives of the Communist Party. The freedom to paint (1938) Once settled in Caldes, he was constrained to spend a month recovering. To pass the time, he took up reading again (The Life of Leonardo Da Vinci by Freud; Rembrandt by E. Ludwig; studies on Matisse and Picasso; Othello by Shakespeare; works by Bakunin on historical materialism...). Meeting the sculptor Manuel Martínez Hugué, or Manolo as he was called, and hearing his accounts of his encounters with Picasso, his friend since 1904, his travels with Braque and Maurice Raynal in Normandy opened up new horizons for Lam. Manolo was also one of the first intellectuals to have recognized “Negro art” and one of its first collectors. The sculptor would talk for hours about African statuary, about the simplification of its forms, its rhythmic reach for the essential, for an expression of essence, of the irrational... It was these discussions that seemed to triumph over all forms of totalitarianism and Manolo who incited Lam to make his way to Paris to meet Picasso. From September 1937, he settled in Barcelona where he came into contact with a much more dynamic artistic community than in the capital. He joined the painting and sculpture section of the Ateneo socialista, which gave him access to a library and a café, and to live models to paint his nudes. Manolo introduced him to the painter Jaume Mercadé and to the photographer Fritz Falkner, who became his new friends. This is where Lam finally set to work and made his definitive break with academicism. Indeed: “The revolution changed my writing and my way of painting,” he once said. With this new sense of encouragement, he set about painting intensively. “I think I must have painted some two or three hundred canvases that I never saw again because, when I left, I gave them to a friend who is now dead.” In the beginning of the year 1938, Lam met Helena Holzer, a young German doctor in chemistry and the director of the tuberculosis laboratory at the Santa-Colomba hospital where she worked for four years. Franz Falkner introduced them to each other in a café on the Lesseps Plaza. The day after Franco's offensive of April 15, which marks the triumph of Fascism and Catholicism, Lam chose to leave Spain behind him.... Anne Egger (Translation by Unity Woddman) |