|

|

|

|

Chronology 1945 - 1951

1945 – 1951 Freedom to travel

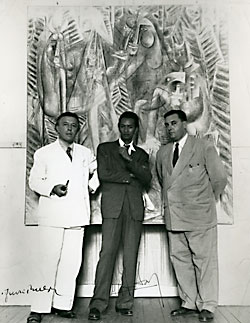

A. Breton, W. Lam, and P. Mabille, Haïti, 1946

In 1945, Wifredo and Helena are invited to Haiti by Pierre Mabille, recently nominated Cultural Attaché for Free France. They attend the inauguration at Haiti's French Institute, set in place in 1941 by Jean Price-Mars and the ethnologist Jacques Roumain to promote cultural diversity... Mabille has set up a library, comprised of books by such authors as Eluard, Desnos, Aragon, Vercors, Gorki, Neruda, Mayakovsky, Lenin, Prévert, Picasso, Métraux, Césaire...Wifredo and Helena arrive in late October with enough work to put together an exhibition. They are quickly joined by André Breton who has come for a cycle of conferences, accompanied by his new wife, Elisa Claro. After the ceremonies of December 7, a number of Haitian artists and writers organize a weekly reunion every Friday at the Savoy cafe, which they attend throughout their stay. In January 1946, the Lam exhibition begins in Port-au-Prince at the Centre d'art, which was opened two years prior by the American Dewitt Peters. The catalogue is prefaced by Breton with “La nuit en Haïti”. The exhibition is a triumph. Magloire Saint-Aude and Hector Hyppolite are captivated by his work. Above all, the event gives a boost to the community of local artists and naive painters whose work will be regularly shown at the center. Voodoo and revolution During the course of his stay, Lam comes to realize to what extent Cuba and Haiti share the same struggle. Since 1945, the hope that the fall of Fascism will lead to the fall of the dictators and authoritarian regimes throughout the Americas is a recurring thought. But it is in Haiti that he personally witnesses an insurrection. The climate of revolt that has been latent during Elie Lescot's dictatorial regime – who was put in place by the United States in 1941 – explodes and in January the whole of Port-au-Prince takes to the streets. After the publication of Breton's speech who openly expresses his opposition “to all forms of imperialism and white brigandage”. The review is forthwith confiscated by the authorities. Leaders of the movement are arrested and hunted down. The youth rally round Gérard Bloncourt, René Depestre, Jacques Stephen Alexis and protest. The army intervenes, topples the Lescot government but cut off the revolutionary youth. A campaign of defamation against Breton ensues who is treated as persona non grata, and especially against Mabille, treated as a spy working for Cuba and Mexico. In the meantime, Lam, Breton and Mabille attend eight voodoo ceremonies – a religion nevertheless outlawed by decree since 1935 – but all a Bembé (the celebration of the Loas religion, with drums, songs and dances in honor of Yemaya). The painter is fascinated. He finds the “wild” and “prodigious” possessions much more impressive than in Cuba; although Breton is less enthusiastic. They return to Cuba in early April to attend the inauguration of Lam's first solo exhibition at the Lyceum in Havana where Mabille gives a conference. Despite his growing recognition, Lam is impatient to return to Europe now that it has been liberated. He will spend only two months in Havana. Far from his studio, he paints very little that year. Cuba – New York (1946 – 1951) Discovery of New York and a disappointing visit to Paris (1946) At the end of June 1946, Wifredo stops over in New York, the biggest city he has ever seen, bathed in a crystalline, immaterial light, but very pictorial. Through Breton, he makes numerous encounters – with Marcel Duchamp and Jeanne Raynal who present him to Nicolas Calas, Roberto Matta, Isamu Nogochi, Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, Sonia Sekula, David Hare, Gerome Kamrowski, Frederick Kiesler... A first contact marked by rich encounters and new friendships. He meets the composer John Cage, who is experimenting with contemporary music. On July 9, he sets off for Europe and reaches Paris after six years of absence. His euphoria is short lived, however. He is surprised by the atmosphere: on the one hand, an artistic world dominated by the diktat of “social realism,” and on the other, the quasi extinction/washed out of Surrealism, now considered a “counter-revolutionary idealism”. While it is a great pleasure to see his friends Picasso and Breton again, they are no longer on the same side. Picasso joined the ranks of the PCF (the French Communist Party) in 1944, while Breton's voice is simple muzzled. In June, he participates in the exhibition at the Galerie Pierre, organized in aid of Antonin Artaud. This is undoubtedly when he meets René Char. The poet's encounter with Lam's works fills him with wonder and is moved to meet the painter in person, whom he finds refined and subtle. They share their experiences of taking up arms – Lam on the side of the Spanish Republicans, Char with the French resistance – and agree that necessity calls for action to take precedence over art. Lam is overjoyed to reconnect with his friend Césaire who invites him to his Sunday reunions on Rue de l'Odéon where Lam is again in the company of Loeb, René Ménil and René Depestre. He meets Jean Cassou, chief curator at the Musée national d'Art moderne. Césaire has entered into politics but without abandoning his inspiration and his art. Wifredo presents Michel Leiris to the new mayor of Fort-de-France and deputy of Martinique, now a member of the Communist Party. Lam decides, nevertheless, to escape his Parisian milieu and, before visiting Italy and Germany in order to see what Europe has become on both sides of the “front,” he takes a short holiday in Cannes. When he returns to Paris, Asger Jorn is there with a project for an international art review which he presents to Picasso and then to Pierre Loeb, and lastly to Breton, on his way back from the United States. But Breton is reticent when presented with the idea of fusing Surrealism and Abstract Art – as Jorn sees it, full of color and spontaneity – which characterizes the new Danish movement. But Breton presents Jorn to Lam who is captivated by his activism who will spend his whole life militating for the total freedom of art. He will later claim that Lam's paintings marked him profoundly and they both share a great passion for music. Lam decides to return to his work in Cuba, taking with him a number of African sculptures from the Kota, Dan, Baolé, Bambera and Dogon tribes, as well as an Oceanic stone ax. A radiant influence from Cuba (1947 – 1948)

Tête Canaïma, 1947

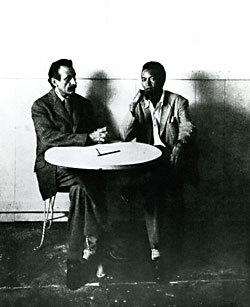

The moment he gets back to work, Lam creates his series of Canaïma. The name evokes the south-eastern region of Venezuela where Carpentier is planning to travel for his newspaper El Nacional, but it is above all the title of a novel by Romulo Gallegos. The author, who wrote it during his exile in Spain (1935), exalts the Aboriginal, set within the jungle of his country and the forest of rubber trees. Gallegos will be elected President of Venezuela the following year, only to be deposed shortly afterward by the junta for his progressive ideas. For the Native Americans, Canaïma is a frenetic god, the principle and cause of all evil, a spirit at times haunts the savannah. Lam's style gains in incisiveness as it evolves and an increasingly esoteric quality develops alongside the African and Oceanic influences. While Helena visits New York during the summer of 1947, Lam goes forward with his work. He has to participate in an exhibition on the other side of the ocean as the Surrealists are organizing the first major Parisian event since 1938. It is being conceived of as a sort of initiatory journey. Lam sends a lithography for the catalogue and, for the labyrinth, an alter dedicated to the “Chevelure de Falmer,” a line taken from Lautréamont's Chants de Maldoror. He is also in the midst of preparing the hanging for his personal show at the Pierre Matisse gallery in New York. Despite the geographical distance, he continues to stay abreast of the cultural involvement of his friends in Paris. Césaire and Leiris have become part of the sponsoring committee for the new review Présence Africaine, founded by Alioune Diop. Its aim is to promote culture in Africa, or rather in the “Africas” – Black Africa, the Caribbean and French-speaking Africa, to breathe new life into a culture that has laid dormant for too long. Lam feels especially enthusiastic about this move which he feels is spawning independence movements throughout the post-colonial world. After a winter in Cuba, Wifredo spends the summer months of 1948 in New York where Helena has found work and decided to settle there. They receive invitations to spend time at Jeanne Raynal and Erwin Nuringer's house and Lam undoubtedly takes an interest in Edgar Varèse's comeback – a friend of Duchamp's. He and Noguchi visit Gorky only a day before he commits suicide (July 21). They also visit Tanguy and make the acquaintances of the artist and architect Naum Gabo, of Frederik Keisler, the artist Maria Martins, introduced to them by Breton and Duchamp. It is Lam's work – seen at the Pierre Matisse gallery – that ultimately stimulates Pollock to study Native American art.

A. Gorky, W. Lam, New York, 1946

When he returns to Cuba in November, Lam joins other artists in creating the Agrupacíon de Pintores y Escultores Cubanos (APEC). After his stimulating encounters with artists in the United States and being well-informed about artistic events in Europe, Lam tries to encourage artists, wherever he happens to be, to cooperate and create artist communities. He learns that Asger Jorn has created the CoBrA group, a group of Scandinavian artists who advocate greater freedom and spontaneity in art with an international and interdisciplinary focus. But it is also engaged art that has a social aim but without linking artistic research to political engagement – an approach that speaks to him for he has always succeeded in being politically engaged without adhering to a particular party and thus avoiding the trap of dictating what is and is not permitted in art. And hence his participation in the CoBrA movement remains a personal one. His production is not as abundant in 1949 as in previous years, but it remains impregnated with the Afro-Cuban oral culture. He works closely with Fernando Ortíz who is preparing the first illustrated monograph on the artist, Wifredo Lam, Y su obra vista a traves de signi ficados criticos. An important essay by Pierre Mabille on the genesis of Lam's work appears in the Magazine of Art. While the local political situation shows little change, the painter no doubt follows closely the proclamation on October 1 of the Popular Republic of China after two years of civil war. Ceramics and separation (1950) Although they have been separated geographically for two years, Wifredo and Helena are on the verge of divorce. In Cuba, the year 1950 proves especially productive and Lam even tries his hand at making ceramics, at the studio in Santiago de Las Vegas, with Mariano Rodríguez, Amelia Pelaez and René Portocarrero. After the monograph by Ortíz is published, the Cuban government decides to offer Lam a grant to study the development of modern art in the United States, France and Italy, allowing him thus to travel abroad. Ever since the war ended, Lam is never in one place for very long. His travels are always exploratory and enriching, both on a cultural and friendship level. In the meantime, he is kept informed of his friends' publications. Lam is especially marked by Césaire's Discours sur le colonialisme and Leiris's “Textes antillais”. Anne Egger (Translation by Unity Woodman) |